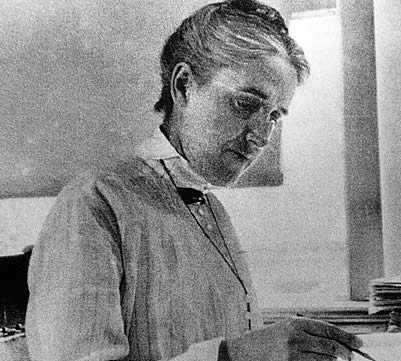

Miss Leonard was a dedicated and frequent observer of the heavens. Her initials appear alongside Lowell’s on page after page of the Observatory viewing logs. In 1904 she was inducted into the Societe Astronomique de France, and in 1907 she published her drawings of Mars in Popular Astronomy. Her unfettered access to the heavens was the exception, however, not the rule – and a privilege given is one just as easily denied. Women of Miss Leonard’s era were not allowed to use the world’s big telescopes. Even with a degree in astronomy, they faced limited career options. Many ended up as “computers” (so named because they computed stellar magnitudes), but instead of observing the stars at prestigious places like Harvard and M.I.T., they studied photographic plates made by male astronomers. This “second-hand look” was their only option, and yet they excelled with it. “Computer” Henrietta Leavitt became famous for measuring changes in the brightness of stars called “Cepheid variables” – stars that fade and brighten in a regular fashion – allowing astronomers to measure distances to far-away objects. She was paid $10.50 a week for her work and received almost no recognition during her lifetime for her substantial accomplishments.

Another “computer,” Elizabeth Williams, a 1903 honors graduate from M.I.T. and the first woman to earn a degree in astronomy there, was hired by Lowell as his chief “computer” and was instrumental in the search for and discovery of Pluto. Like the female “computers” of her era, Miss Leonard’s most original thinking about the stars and planets comes after she is banished from the dome. |