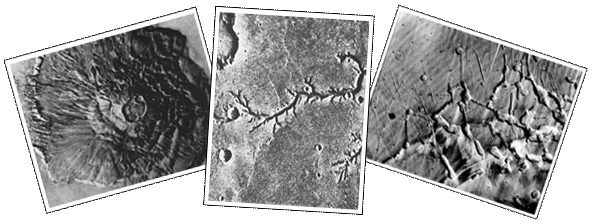

Mars, as photographed by black-and-white television cameras with slow-scan vidicon tubes (very low definition by today's standards), looked bland and uninspiring – until JPL’s Image Processing Lab had its way with the data.

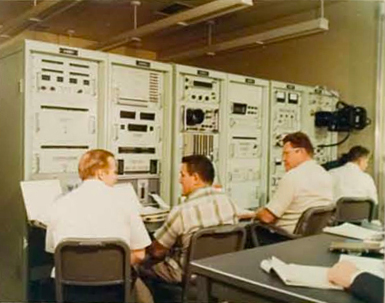

Early techniques used room-sized computers to assist in clarifying and enhancing the images of Mars and Venus as recorded and transmitted by the Mariner space probes – but only within severely restrictive parameters designed to maintain the integrity of what the onboard cameras had recorded.

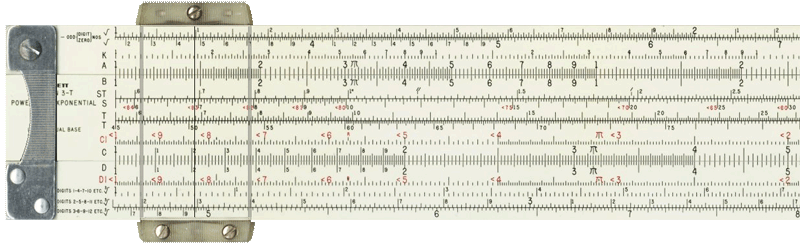

Among the permissible adjustments were the removal of static and other transmission noise and the stretching of contrast to emphasize depth or detail. A grid pattern of dots called reseau marks, engraved on the camera lens, made geometric corrections possible. The process was tedious – computer scientists used slide rules to write algorithms, fed them into the computer and waited – sometimes for hours – for the computer to process the information and for the monitor to display the results. |

|||||

|

|||||

| Some of the best Mariner 9 images, after processing: mega-volcano Olympus Mons, evidence of past water-flow, and the detailed edges of gigantic crater Valles Marineris. None of these features were known prior to the Mariner 9 mission. |